|

Life & work of Saadat Hasan Manto - III

Minto’s two set of stories about the Partition

According to Prof. Ashok Bhalla, the author of Life and Works of Saadat Hasan Manto(1998), Manto’s first set of stories about the Partition, like “Toba Tek Sing, Thanda Gosht and Siyah Hashiye were written soon after 1947. Manto wrote a second set of stories about the Partition between 1951 and 1955. According to Bhalla:

“The first set of stories is vituperative, slanderous and bitterly ironic. They are terrifying chronicles of the damned that locate themselves in the middle of madness and crime, and promise nothing more than an endless and repeated cycle of random and capricious violence in which anyone can become a beast and everyone can be destroyed.

Manto uses them to bear shocked witness to an obscene world in which people become, for no reason at all, predators or victims; a world in which they either decide to participate gleefully in murder or find themselves unable to do anything but scream with pain when they are stabbed and burnt or raped again and again. Manto makes no attempt to offer any historical explanations for the hatred and the carnage. He blames no one, but he also forgives no one. Without sentimentality or illusions, without pious postures or ideological blinders, he describes a perverse and corrupt time in which the sustaining norms of a society as it had once existed are erased, and no moral or political reason is available.”

Bhalla argues that unfortunately, Minto’s second set of stories about the Partition are neither as well known and documented, nor as systematically analyzed as the previous ones. “They are, however, significant stories because, together with the earlier ones, they create out of the events that make up the history of our independence movement, an ironic mythos of defeat, humiliation and ruin. If the first set of stories are is fragmentary, spasmodic and unremittingly violent; the stories of the second set are more complex and more concerned with the deep structural relationship between the carnage of the Partition and human actions in the past. While rage and hopelessness still mark the second set of stories, and fear and violence still bracket the beginning and the end of each one of them, the past is more intricately braided into the texture of the main narratives than it is in the first set of stories, and the incidents are more symbolically charged.”

In September 2012, a two-day seminar was held in New Delhi to commemorate the birth centenary of Saadat Hasan Manto. It was chaired by Professor Ashok Bhalla, who argued that too much focus had been given to Manto’s works in which he had documented the trauma, pain and horror of Partition. His works which have archived the syncretic history of the sub-continent and highlighted its devastation in post-partition Pakistan have largely been ignored, he argued. “Take Manto’s Dekh Kabira Roya, in which he has imagined Kabir walking through the streets of Lahore in the post-Partition Pakistan and crying after seeing the treatment of an idol of Lakshmi at the hands of fundamentalists. With much pain and a sense of loss, he repeatedly highlighted instances of cultural blasphemy happening during his time, some thing which tends to be ignored.”

Terming the seminar an attempt to re-read Manto in all the unexplored contexts, Prof. Bhalla said: “It is an attempt to see all these aspects of Manto’s writing which have largely been unexplored in greater details. It was attempted to appropriate Manto as an apologists for Pakistan and as a Muslim writer of and for Pakistan. Whereas the reality is just the opposite.” Prof. Bhalla wondered what explained this new love for Manto, when until the past two decades people didn’t talk about him, neither in the literary circle nor in the popular narrative because he raised “uncomfortable questions.”

He argued that Manto had all his life criticized the middle class highlighting its moral corruption and hypocrisies but now the same class has appropriated him as an “entertainer” ignoring the uncomfortable questions which are part of his writings. “Manto has been co-opted by the middle class entertainment industry. These days you have plays on Manto’s life which evoke laughter. There is no talk at all of uncomfortable questions and serious problems which are part and parcel of his writings.” [4]

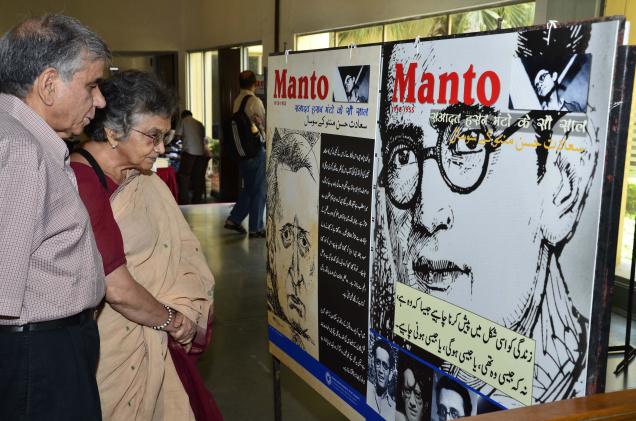

[Visitors at the exhibition on Saadat Hasan Manto at Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, Teen Murti House, in New Delhi on Friday. Courtesy The Hindu]

Ludhiana Personality

Saadat Hassan Manto was born in Paproudi village of Samrala, in the Ludhiana district of the Punjab. Ludhiana district’s business website has listed him in the Ludhiana Personalities with a detailed write up about his life and work [5]:

During his controversial two-decade career, Manto published twenty-two collections of stories, seven collections of radio plays, three collections of essays, and a novel. He is best known for his short stories – over 250 in 2 decades, many of which have been enacted in plays and films.

The film studios at last recognized his gift for story writing and he worked on several film scripts of Keechad, Apni Nagariya, Begum, Naukar, Chal Chal Re Naujawaan, Kisaan Kanya, Ghamandi, Beli, Mujhe Paapi Kaho, Doosri Kothi, Shikaar, Aath Din, Aagosh, Mirza Ghalib, etc.

His pride was seriously hurt when the very best samples of his craft, "Kali Shalwar," "Dhuan" (1941) and "Bu" (1945) were tried under Section 292 of the Indian Penal Court. Ironically, these stories were some of the best that Manto had written so far. Even though he was acquitted in the end in each of these cases, he could neither forgive nor forget the humiliation of being tried in the same category as exhibitionists who showed private parts to little girls on the street.

The only paper that published Manto's articles regularly for quite some time was "Daily Afaq", for which he wrote some of his well known sketches. These sketches were later collected in his book Ganjay Farishtay (Bald Angels). The sketches were of famous actors and actresses like Ashok Kumar, Shayam, Nargis, Noor Jehan and Naseem (mother of Saira Bano). He also wrote about some literary figures like Meera Ji, Hashar Kashmiri and Ismat Chughtai.

The first story he wrote after a long time was "Thanda Gosht" (1950), arguably the best piece of imaginative prose written about the communal violence of 1947. It is comparable only with Manto's own anthology Siyah Hashiyay, a light veined treatment of the psychology of communal violence through a series of small anecdotes. "Thanda Gosht" was published in a literary magazine in March 1950, and the magazine was immediately banned. This time the District Court sentenced Manto to three months of rigorous imprisonment and a penalty of Rs.300. The High Court revoked the sentence of imprisonment but retained the penalty.

Two other stories of Manto were also charged for obscenity by the federal government, namely "Khol Do”, a masterpiece on violence against women, and "Oopar, Neechey Aur Darmiaan (1953)" a minor farcical essay about married couples' attitude towards sex. That brought the total of Manto's condemned stories to six, bringing him a name as a writer on sexuality. Thus, it hampered a comprehensive appreciation of his work both by his opponents and his supporters, as both sides kept their focus on proving or disproving the charges of obscenity.

The reality is that the collected works of Manto capture a far wider range of issues, and sexuality is just one of them. Manto focused on the spark of life in the human being, the creative force of individuality that urges all kinds of people to break free of the exterior constraints at least once and respond to the unique inner voices of their souls.

On a cold winter morning of 18 January 1955 in Lahore, Saadat Hasan Manto found himself bleeding through the nose. An ambulance was called to take him to the emergency. The doctor who greeted him at the hospital turned to his companions and said, "You have brought him to the wrong place. You should have taken him to the graveyard”. Establishing the cause of death wasn't a matter of medical expertise but simple common sense. Someone living on more than a full bottle of undiluted bootleg liquor and two slices of bread everyday for many years could hardly expire of anything but Liver Cirrhosis.

Continued on page 4 of 4 pages

|